One of the central conundrums for writers of realistic novels during the second half of the nineteenth century was how to describe boredom in a way that was not boring in itself, how to describe the mind-numbing blandness the ordinary life of the ordinary citizen had become without putting readers to sleep. At the end of the 20th century, J.J. Voskuil’s monumental (over 5,000 pages in seven volumes) novel Het Bureau showed that this was no longer a concern, and that by then it had become entirely possible to describe boredom in an utterly boring way and to not only get away with it, but to even produce a national bestseller.

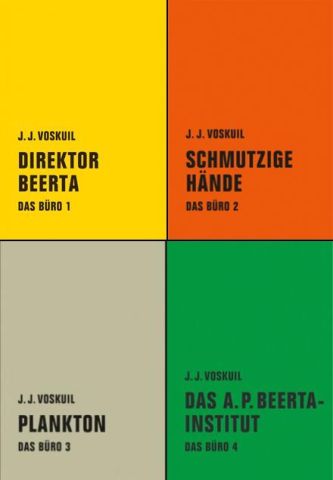

This might sound as if I disliked the novel (of which I have read the first four volumes so far, which is as far as the German translation has progressed at the time at which I’m writing this), but actually the contrary is true: Het Bureau describes the boring everyday lives of boring people doing boring things (mainly) at work and (occasionally) at home, and it does so without any kind of plot to liven things up, using a mostly boring language whose gray blandness is entirely suitable to its subject. Almost 3,000 pages of this (not even to mention the 5,200 of the complete novel) should have been completely unreadable and about as exciting as learning the phone book by heart, but J.J. Voskuil mysteriously manages to achieve an alchemy by which this massive assault of boredom actually becomes transmuted into something compelling and highly entertaining.

This might sound as if I disliked the novel (of which I have read the first four volumes so far, which is as far as the German translation has progressed at the time at which I’m writing this), but actually the contrary is true: Het Bureau describes the boring everyday lives of boring people doing boring things (mainly) at work and (occasionally) at home, and it does so without any kind of plot to liven things up, using a mostly boring language whose gray blandness is entirely suitable to its subject. Almost 3,000 pages of this (not even to mention the 5,200 of the complete novel) should have been completely unreadable and about as exciting as learning the phone book by heart, but J.J. Voskuil mysteriously manages to achieve an alchemy by which this massive assault of boredom actually becomes transmuted into something compelling and highly entertaining.

I couldn’t really say how he accomplishes it, and from interviews I have read I received the impression that the author doesn’t quite know himself – his explanation that office life is something everyone knows from their own experience and can hence relate to seems not very convincing to me, as there are lots of novels about all kinds of things everyone can relate to which aren’t particularly successful either esthetically or commercially. I think we get closer to the hear of the matter if we consider Het Bureau as part of a novelistic trend that has become very popular in Europe and beyond in recent years: Multi-volume novels that are at least partly autobiographical with a slice-of-life approach to their mundane subject matter and combining an unflinching look at human foibles and weaknesses with an apparently artless, matter-of-fact language. I’m thinking of Elena Ferrante’s Neopolitan Novels and Knausgaard’s My Struggle both of which were huge popular successes not just in their native country but internationally as well, and I’m somewhat surprised that Het Bureau has not been translated into English yet as it clearly belongs to the same category of novel.

Het Bureau, however, while based on the author’s own experiences, is the least personal of those – even though it does have a main protagonist in Maarten Koning, and we learn quite a bit about his private life in the course of the narrative, the novel’s emphasis is on an ensemble cast, and a very huge ensemble at that. At the centre is of course the titular office, the “Institute for Cultural Anthropology” (I’m not quite sure whether that is the correct English translation – it’s “Volkskunde” in the German version, a term which even today retains some traces of its Nazi origins, something which plays an important part in Voskuil’s novel as well), and the novel follows its vagaries over the course of 30 years. The model for Voskuil was not confessional literature then, and the literary progenitor looming in the background appears to me to be not so much Proust but rather Balzac. Indeed, I think in a way Het Bureau is the Comédie Humaine of the twenty-first century – except that Voskuil’s backstabbing bureaucrats are but a pale shadow of Balzac’s larger-than-life characters. The power-hungry, morally ruthless members of the rising bourgeoisie have all joined the civil service and turned into narrow-minded quibblers who scramble for a place in a committee, plot to overthrow their superiors or fake chronical illnesses – mean and petty rather than evil, the wolves and sharks of the nineteenth century have mutated into Chihuahuas and guppies.

Possibly one might even have to go farther back to find something comparable to Het Bureau – the afterword to the second volume mentions novels about civil servants being a a genre in ancient China. I know next to nothing about ancient (or, indeed, contemporary) Chinese novels, but am seriously considering to remedy this once I’m done with the translated volumes of Voskuil. Since finishing the fourth volume of Het Bureau, I have read The Scholars by Wu Jingzi, a Chinese novel from the early 18th and supposedly a satire on the feudal examination system in ancient China, and there are indeed quite a few parallels one could draw. Parallels, though, which one could just as well draw between Wu Jingzi and Balzac, which is where things would start to get really interesting, in so far as one could start wondering just how big a debt Western realism owes to the Chinese novel… but that would probably lead us just a tad too far astray.

Back to Voskuils and Het Bureau then, which despite its possible roots in classical and undoubted parallels in contemporary literature offers a reading experience quite unlike anything else. Mainly, I think, it is the combination between its vast scope with a simultaneous attention to minute detail which produces a weird, hypnotic effect on the reader, an effect which is even further enhanced by the constant repetition of events and endless circularity of arguments – Philip Glass should turn this into an opera, or even better a series of operas, the Ring of minimalist music. In fact, similar to Glass’ music, even as nothing new ever seems to happen, the same persons doing the same things over and over or refusing to do them again and again with always the same arguments, even as the novel’s main protagonist despairs of the mind-crushing monotony and sameness, there are shifts and changes happening throughout the volumes. True, they occur at about the speed of continental drift, but they are noticeable – while the first volume of the novel still gives a large amount of space to the actual work the employees of the Institute do, this moves increasingly into the background as the novel progress, to be replaced by intritues both inside the office itself as well as the wider world of Europena academia. In parallel to that, Maarten Koning changes, too; while he never (not until the end of volume four at least) ceases to view the work he is doing as essentialy pointless and devoid of any real purpose, that work takes up more and more of his life, to the continued (and very vocal) chagrin of his wife who finds her time with her husband being eaten up by his office life.

Het Bureau spans several decades, and during that time, a whole host of people come and go, none of which is (and that includes the protagonist and alter ego of the author, Maarten Koning) particularly likeable – even people who appear nice when we encounter them for the first time eventually become ground down by the mindless apparatus of the “Institut für Volkskunde” and invariably end up showing their unlikable, sometimes even their outright nasty side. While not every single member of the novel’s huge cast is equally memorable, many of them will stick in the reader’s memory. To name just two of those, there is Director Beerta, the founder of the Institute and initially Maarten’s boss – he is basically a windbag with a knack for ingratiating himself with the winning side in any argument. He is utterly without scruples about backstabbing even his closest colleagues, but at the same time possesses an undeniable charm which lets him get away with it again and again. Utterly without charm, on the other hand, is Bart Asjes, one of Maarten’s subordinates, and quite likely the most unlikable character I have ever encountered in any piece of fiction. He not only refuses to do any work, but gets everyone who tries to make him do anything involved in lengthy, pointless arguments; he is always opposed on general principle to everything anyone else proposes, but of course never has anything constructive to offer in return. One really has to read the novel to appreciate just how much of a pain he is, and it indeed in things like this characterisation of Bart Asjes where Voskuil’s method pays off gloriously – after having been mercilessly exposed to one of his suadas for the dozenth time, the reader eventually starts to hate Bart just as much as Maarten does, and I caught myself several times grinding my teeth at the prospect of him sabotaging yet another entirely reasonable suggestion. By sparing the reader nothing, by elaborating every painful detail and then repeating it over and over again, the reader gets drawn into the story just as Maarten is swallowed up by the office, and the unfurling of events ultimately achieves an almost physical impact, even in spite of the mostly bland prose.

This again makes reading Het Bureau sound like an unpleasant experience, so let me hasten to add once again that it is emphatically not so, but to the contrary remains highly enjoyable even over 3,000 pages of utter meaninglessness. This is at least partially due to the novel being quite funny – not in a comedy way, nothing here is played for laughs, and it can be very depressing at times. There is no comedic mise-en-scène here at all, but the bare factuality of what happens or does not happen is often so utterly absurd that the reader finds himself laughing out loudly even while blinking in disbelief at what they just read. Again, this is something one has to experience and which can’t really be summarized as the effect is achieved by the peculiar way the novel unspools its narrative. In fact, I could not help but wonder whether Het Bureau really should be considered a novel and not rather a work of Cultural Anthropology, which investigates and preserves the strange rituals of 20th century academics in the Netherlands just as those academics examine Dutch folklore. But then, the novel being what it is, the two are maybe not mutually exclusive and Het Bureau is a novelistic museum which we do not so much read as wander through, gawking, gasping and giggling at the bizarre way the inhabitants of the late 20th century allowed their work to consume their life. And viewed like that, it is probably not at allt strange but seems like an always intended part of Het Bureau that when the original for the novel’s Institute was moving, its staff were giving guided tours to the public while wearing tags with the names of their counterpart novel characters.

Oh my God, Heloise, I never cease to wonder at your courage in plunging into these kinds of books. My initial reaction was: what kind of world can we be living in, if it’s “possible to describe boredom in an utterly boring way and to not only get away with it, but to even produce a national bestseller”?!!! But I can see how the repetitive quality of the book would perhaps produce its own strangely compelling and hypnotic quality.

Nevertheless, I don’t think I am going to try this, even if it *is* translated into English – I don’t have your patience or your admirable thirst for different or conceptual stylistic approaches – but it’s certainly interesting to read about it. And of course to see how this prompted you to move on to the Chinese project. (I know I’m reading your posts in the wrong order.)

It’ll be interesting to see whether your feelings change as and when the next three volumes are published. What an epic work this is!

I hope it is a “when” and not an “if”, as the release date of the fifth volume has just been pushed a back a month. In spite of this, I’m actually thinking I should have waited for all seven volumes to be translated and then read all of them in one go, as this really is one long novel. And I probably make it sound worse than it is for dramatic effect – it really is a comparitively easy and quite enjoyable read. After all, this apparently was a huge bestseller in the Netherlands, if you don’t want to take my word for it. 😉

In spite of this, I’m actually thinking I should have waited for all seven volumes to be translated and then read all of them in one go, as this really is one long novel. And I probably make it sound worse than it is for dramatic effect – it really is a comparitively easy and quite enjoyable read. After all, this apparently was a huge bestseller in the Netherlands, if you don’t want to take my word for it. 😉